Grbavac v Vujcich relates to an application to recall probate on the basis that the deceased lacked testamentary capacity when he executed a codicil to a 2004 will in 2013. At the time of his death Joseph Grbavac’s estate was valued in excess of $10 million.

The 2013 codicil reduced the number of executors, changed certain bequests and removed three beneficiaries. Mr Grbavac (referred to in the judgment as Mr Joseph) had no children. As noted at [16] and [17]:

[16] Provided will-makers have testamentary capacity, and the obligations imposed under the Family Protection Act 1955 and the Law Reform (Testamentary Promises) Act 1949 are not engaged, they are free to dispose of their property as they wish. Their dispositions need not be fair; indeed, they may be brutal as to their outcome.

[17] The only statutory obligations Mr Joseph owed were to his wife under the Family Protection Act. No issues are raised in that regard. So, provided he had testamentary capacity he was free to dispose of his property as he wished. The law on testamentary capacity is well settled.

As noted in Bishop v O’Dea at [3]:

[3] In probate proceedings those propounding the will do not have to establish that the maker of the will had testamentary capacity, unless there is some evidence raising lack of capacity as a tenable issue. In the absence of such evidence, the maker of a will apparently rational on its face, will be presumed to have testamentary capacity.

[4] If there is evidence which raises lack of capacity as a tenable issue, the onus of satisfying the Court that the maker of the will did have testamentary capacity rests on those who seek probate of the will.

[5] That onus must be discharged on the balance of probabilities. Whether the onus has been discharged will depend, amongst other things, upon the strength of the evidence suggesting lack of capacity

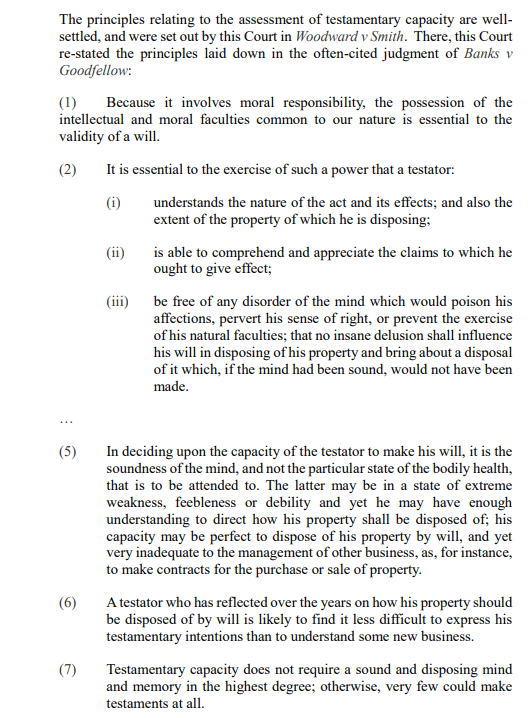

With respect to the elements of the law of testamentary capacity, reference was made to the indicia set out by the Court of Appeal in Loosley v Powell at [19]:

The absence of informative contemporary records was problematic. As noted at [27] “…The legal records of relevant events are not as good as might be expected. Some such events were not recorded at all. Other records, such as the legal notes Mr Lucas made at the time of his attendances with Mr Joseph, are cryptic and impossible to understand without further explanation. Often the only idea of how long a particular attendance on Mr Joseph may have lasted has to be gained from the time recorded in the fees ledger.

As noted at [28]:

Accordingly, an understanding of the relevant events leading up to the execution of the 2013 codicil must be gained from a forensic analysis of the available evidence set out in chronological order; this evidence comprises a mix of documentary evidence, circumstantial evidence and the recall of Mr Lucas and Ms Bullot, as well as other witnesses, of events, sometimes undocumented, that happened some six or

more years before the trial. No doubt this has contributed to the parties’ dispute. Had clear and fulsome file notes been made at the relevant times they may have reduced if not removed the scope for dispute. But that is not what happened.

Chronology of relevant events

- Mr Joseph was 83 when he executed the 2004 will, 87 when he executed the 2008 codicil and 92 when he executed the 2013 codicil

- In his later years Mr Joseph had become irritable and frustrated with the limitations his age and deteriorating health had imposed on him

- Mr Joseph had poor eyesight following a failed cataract operation and required the use of a magnifying glass to read

- By 2011 Mr Joseph had poor hearing. However, he did not like others to know he was hard of hearing and he would act as if he could hear when he could not

- From 2012 Mr Joseph required a high level of personal care

- From 2012 medical reports indicated deterioration in insight and vagueness

- Cognitive screening was not carried out for various reasons

- The lawyer Mr Lucas met with Mr Joseph at his home from 2010 onwards, usually together with Ms Bullot, a legal executive who had a long-standing relationship with Mr Joseph

2011 draft

In 2011 a new will was drafted. As noted at [43] and [44]:

Later in 2011 Mr Joseph had thoughts regarding settling a charitable trust. As noted at [45] “… Mr Lucas agreed that Mr Joseph had it in mind to give money to a charity he established rather than to family. However, this idea was not pursued to any great extent, possibly because Mr Lucas did nothing to take it any further.”

The 2011 will was not executed.

In 2012 Mr Joseph entered into new enduring powers of attorney. The lawyer’s notes regarding meeting with Mr Joseph to obtain instructions were somewhat cryptic. A letter sent to Mr Joseph with the enduring powers of attorney did not as noted at [52] “… explain the effect of the powers of attorney and Mr Lucas accepted in evidence that he made no note of having given this explanation to Mr Joseph when he visited him on 2 March 2012.” Further Mr Lucas did not know that Mr Joseph had cataracts in both eyes. Regarding the certificate he gave in respect of the EPOAs Mr Lucas in recorded at [53] as stating that “… his understanding was that the certificate on the powers of attorneys did not require him to enquire as to whether Mr Joseph understood this document.”

In a further meeting, under the heading in the judgment of “Mr Joseph is “bullied” into signing a power of attorney, Duffy J states at [54] that “What is notable about this meeting is that the file note made at the time records Mr Joseph had doubts about Mr Behrent holding a power of attorney, yet at that meeting he signed powers of attorney which appointed Mr Behrent to this role.”

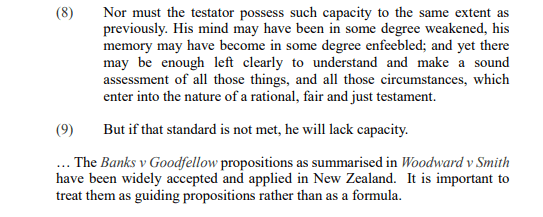

The Court’s view regarding the attendances with respect to the powers of attorney, in the context of Mr Joseph’s lawyer stating that “there was a need to “draw a “sometimes a line needs to be drawn” was sumarised at [60] in the following terms:

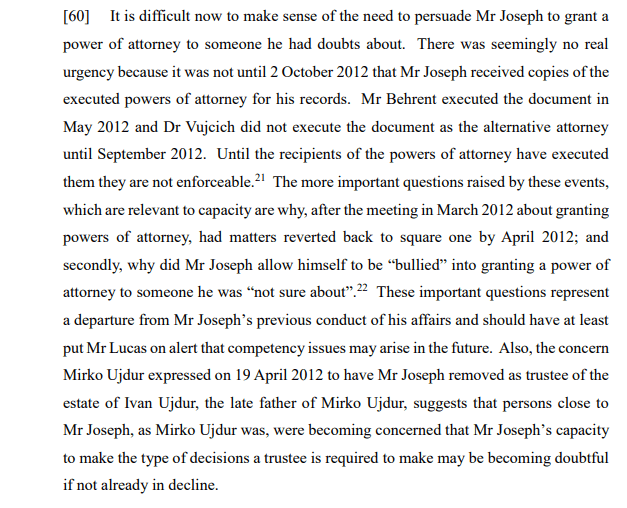

Further meetings followed. In September 2012 Mr Lucas file noted a phone call with Mr Joseph’s doctor expressing concerns regarding Mr Joseph’s capacity:

Importantly, as set out at [64]:

The attendance on 24 September 2012 stands out from other attendances on Mr Joseph. The experience raised concerns for Mr Lucas about Mr Joseph’s capacity to the point where Mr Lucas contacted Dr McDonald. Her understanding of their discussion was that they agreed there should be no will changes, whereas his understanding was that any drastic will change may signify issues regarding capacity.

Given the changes Mr Joseph had already been contemplating up to this date, the discussion with Dr McDonald should have prompted Mr Lucas to make enquiries with Mr Joseph about organising a capacity assessment by a medical expert or for Mr Lucas as Mr Joseph’s solicitor to undertake this task himself in conformity with the principles laid down in Banks v Goodfellow. The road map for a solicitor in Mr Lucas position to follow, which encapsulates the Banks v Goodfellow principles, was set out in Woodward v Smith. As at 2012 this law was well established. However, no such steps were taken. Instead matters continued as before with Mr Lucas making subsequent attendances on Mr Joseph to discuss will revisions.

The events of 2011 and 2012 are summarised by Duffy J as follows:

The 2013 codicil

In 2013 Ms Bullot assumed sole responsibility for attending on Mr Joseph. No explanation is given for this. These culminated in the execution of the 2013 codicil. However, the absence of file notes made assessing the progress of matters problematic. It was Ms Bullot’s evidence that she destroyed file notes after actioning them.

Document 909

Duffy J’s conclusion regarding the evidence was that as stated at [113]:

What is apparent from this evidence is that for reasons for which there is no given explanation Mr Joseph was changing his mind about who would be executors/trustees and beneficiaries in the early part of 2013. Nor is there any contextual evidence that could explain why his views on this topic were changing.

Further as noted at [140]:

The absence of contemporary records also means there is no contemporary record of Ms Bullot concluding that there was no reason to doubt Mr Joseph had testamentary capacity to execute the 2013 codicil.

The lack of proper record keeping is criticised in the context of the value of Mr Joseph’s estate The decision to amend the earlier will by codicil rather than enter into a new will was examined, but not able to be answered satisfactorily rather than to suggest a concern regarding capacity due to there being a shorter and more readily understandable document. See [159].

Negative views were formed regarding professional comptetency.

Evidence of capacity

A number of witnesses gave evidence regarding Mr Joseph’s capacity. These witnesses included people in regular contact; people with less contact; Mr Joseph’s doctor and expert medical witnesses. As noted at [299]:

[299] Dr Casey completed her evidence with the acknowledgement “I can’t put a diagnosis on it because there actually isn’t the assessment and there isn’t sufficient collateral history for me to say as a clinician that this is what the diagnosis was”. This acknowledgement is probably a fair summation of the evidence from both experts.

Finding

[300] The constraints on the experts’ ability to offer opinion evidence limits the helpfulness of this evidence. It establishes that on the available evidence it cannot be said that Mr Joseph had a medically diagnosable cognitive impairment. However, the evidence from Dr Duncan also shows that hypothetically someone in Mr Joseph’s condition may have been suffering from impaired cognition. The various conditions that he suffered from can be associated with cognitive impairment. Therefore, the expert evidence cannot exclude him having a cognitive impairment.

Golden Rule

Vacuum of knowledge

Duffy J’s conclusion resonates with the decision in Murray v Murray where the High Court found that capacity had not been confirmed noting:

“This is not a credibility case. The witnesses who gave evidence before me, Dr Cattin, Mr Dale Murray and [the solicitor], were all credible witnesses. The conclusions I reach are informed by their evidence and by an analysis of their evidence which reveals the information vacuums which existed.”

Duffy J’s conclusion reads as a what not to guide.

Theresa Donnelly will be presenting a contemporary consideration of capacity in the context of enduring powers of attorney at the Elder Law Conference on 28 May 2025.

References

- Grbavac v Vujcich [2020] NZHC 1953

- Loosley v Powell [2018] NZCA 3, [2018] 2 NZLR 618 at [19]

- Bishop v O’Dea CA 120/99, 20 October 1999

- Banks v Goodfellow (1870) LR 5 QB 549

- Woodward v Smith [2009] NZCA 215

- Murray v Murray [2012] NZHC 545

Discussion

No comments yet.