Kermit the frog sang “It’s not easy being green.” It’s not always that easy being a beneficiary either. The Sesame Workshop advises that the song is about “… knowing who you are, realizing your own worth and dignity, and becoming more content and comfortable within yourself.” Whether this will help any beneficiaries of discretionary trusts find solace as they navigate this role is another question altogether.

As set out in the Trusts Act 2019 at section 6(2) “As a fiduciary, each trustee owes duties and is accountable for how the trust property is managed and distributed.”

But what does this really mean? Are trustees required to consult with beneficiaries? In Ashley Dawson-Damer v Grampian Trust Company Limited the Board of the Privy Council states at [71] that “it was common ground that a trustee is not in breach of duty by failing to consult with a potential beneficiary.”

The Royal Court of Jersey decision In the Matter of the Representation of N expands on the concept of consultation. While the application caused the Court some difficulty the end result was that Court did bless a decision where the trustee essentially reneged on what had been communicated to a beneficiary, which was that that the trust has been “notionally split” into 2 parts, one for A and one for B. Subsequently a different course of action was adopted as set out at [28] to [31]:

- In broad terms, the mathematics are as follows. The trust assets available for distribution were £3.4M to which, for the purpose of calculating the 50/50 notional division, had to be added to the £1.9M B (and his children) had already received since the settlor’s death, giving a total of £5.3M.Each notional fund was therefore half this amount, namely £2.65M. Of his notional share, B (and his children) had already received £1.9M, leaving £750,000 available for his children. By deciding to distribute £1.5M to his children (£500,000 to C and £1M to the US trust) N had “taken” £750,000 out of A’s notional share.

- Neither A nor his advisers had been given notice of the change in the Trustees’ thinking or that a meeting was taking place at which these distributions were under consideration. M informed both A and B of the decision by e-mail on 22nd January, 2010. In his evidence before us, (although not in his affidavit) A said he had learned of the decision in a phone call to N that day and had spoken to M before the e-mail was sent to him. He said that M was abrupt and slightly aggressive in his manner, in order, he felt, to shut him up and have him accept the decision. He said he spoke to him again a week later. M had no recollection of these calls, but denied that he would have treated him in such a manner. We accept A’s evidence that such calls did take place and we think it is likely that M would have been somewhat defensive in the light of N’s decision to use part of A’s notional share to benefit B’s children against his wishes.

- A took no action for some two months before forwarding M’s e-mail to his solicitor S on 25th March, 2010. In the meantime, N had proceeded to implement the decision in part, by distributing £500,000 to C on 19th March, 2010. S’s reaction, as expressed in his telephone call with M of 11th June, 2010, was that N had been bullied and threatened by B. In his letter of 17th August, 2010, to N, he highlighted the abrupt and significant change between the “final decision” of N as set out in the minutes of the meeting of 12th May, 2008, and the decision of 14th December, 2009. N was put on notice that if any part of the decision was implemented, A would make an immediate

application to the Court. N pre-empted that threat by itself bringing this application by representation dated 24th November, 2010.

- At a directions hearing on 22nd March, 2011, the Court raised the issue of whether it was open to it to sanction a decision that had been part performed but none of the parties sought to argue against its ability to do so. N wanted the application heard and accepted the risk that if the Court declined to bless the decision, the reasons put forward by the Court may have an adverse impact upon its ability to defend proceedings subsequently brought in relation to that part of the decision that had already been implemented, namely the distribution to C.

While N’s behaviour was considered “regrettable” as set out at [54] and [55]:

- The first principle is that trustees must not fetter the future exercise of their discretion, but must exercise their judgement according to the circumstances as they exist at the time. A trustee cannot pledge himself or undertake beforehand as to the mode in which a power will be exercised in the future (see Lewin 29-204). We agree with Mr MacRae and Mr James that the minutes of the meetings in May 2008 and March 2009 simply reflect the thinking of the trustee and Protector at those times, and did not purport to and cannot fetter the future exercise of the trustee’s discretions. Nothing was done that had any legal effect. No appointment into two funds was made. No distributions were made. The division was “notional” i.e. existing only in thought or imaginary (see The Shorter English Dictionary). What Mr Robertson characterised as decisions were nothing more in law than a record of N’s thoughts at the time. Throughout the period up to

December 2009, A remained a member of the class of beneficiaries with no greater interest in the trust fund than any of the other beneficiaries. Whilst N should no doubt take into account its previous thinking, which M and O said it did, it cannot be fettered by such previous thinking. When it came to the decisions to be made in December 2009 it was required to exercise its judgement in the circumstances existing at that time which included all of the factors mentioned by M and O, irrespective that some of those factors may have been known to N since before the meetings in May 2008 and/or March 2009.

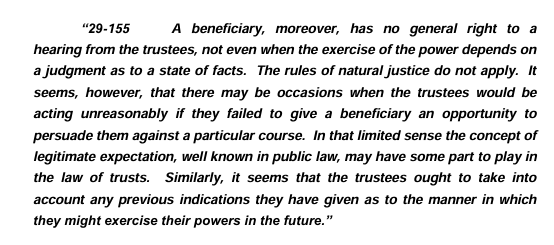

- The second principle is that the rules of natural justice in the traditional sense do not apply. Quoting from Lewin:-

While the Court was not impressed with how matters played out, nevertheless the decision was approved as follows:

- We therefore sanction the decision of N taken on 14th December, 2009. In doing so we wish to say this. Whilst we have found that the decision was within the bounds of rationality and therefore to be sanctioned, we were very troubled by the high handed manner in which we feel N had treated A and his advisers. It was indeed regrettable that having met with A and his advisers in February 2009 and engaged in the kind of discussions reflected in the minutes of that meeting, N should then have proceeded to deal with the trust fund in this way without informing A and his advisers of its intention to do so. A would always have been disappointed with the decision that was made, but the manner of his treatment can only have added to his sense of grievance.

Importantly as set out at [63]:

- The Court had to remind itself of its limited role and the legal principles that apply to discretionary trusts. The focus is not upon the expectation of the beneficiary but upon the information available to the person who the settlor has appointed as decision maker. There is no authority for the importation into trust law of a right to be heard or consulted. Such rights would potentially render trusts unworkable.

To conclude, it’s not easy being green or a discretionary beneficiary.

References:

- In the Matter of the Representation of N [2011] JRC 135

- Ashley Dawson-Damer v Grampian Trust Company Limited [2025] UKPC 32

- Lewin on Trusts, 20th ed (2020), Vol II, para 28-116;

- Ashley Dawson-Dalmer v Grampian Trust Company Limited 2015/CLE/gen/00341

- Sesame Workshop

Discussion

No comments yet.